The life and political work of Adelaide Tambo, especially during the thirty years she was exiled in London offers an insight into the role of women within the anti-apartheid struggle. In her working life, Adelaide Tambo was a nurse, and she carried a commitment to care into her politics.

Adelaide Tambo and the politics of care

'Ma' Tambo

Adelaide Frances Tshukudu is best known as Adelaide Tambo (or just ‘Ma Tambo’), wife of the ANC President Oliver (O.R.) Tambo. She was, however, an important anti-apartheid activist and leader in her own right. A commitment to fighting for the rights of South African women was central to her activism and she developed an approach to her political work which placed relationships of care at its heart. This approach can be found in her earliest political work in South Africa, the role she played in exile in London, and when she returned to South Africa after the end of apartheid. In 1994 she was elected to the South African Parliament as an ANC MP, serving on the Housing, Health, and Welfare committees. She also became national treasurer of the ANC Women’s League.

Image: Adelaide and Oliver Tambo on their wedding day (courtesy and copyright Oliver & Adelaide Tambo Foundation/ Tambo Family Archive)

Adelaide Tshukudu was born into a Sotho-speaking family in Vereeniging, where her father and uncles worked in the local steel mill. She was brought up in the Methodist church but became a Catholic while at primary school. Adelaide was initially politicized at the age of 10 when she saw her grandfather being beaten and brutalised by the police.

Adelaide and Oliver Tambo first met in 1946 at an ANC Youth League meeting, when Adelaide was 17 years old, still a pupil at Orlando High School in Soweto, but also working as a courier for the ANC. The pair wrote to each other for a while after this first meeting but did not become a couple until nearly seven years later, by which time Oliver was working in legal practice with Nelson Mandela and Adelaide was finishing her nursing training.

For both Adelaide and Oliver, religious faith and political convictions were closely entwined. But when Oliver proposed in 1954, it took two years for them (and their families) to negotiate and reconcile both their ethnic and religious differences. At the time, Oliver was considering training to become an Anglican priest. Eventually, Adelaide converted to Anglicanism to smooth their path to marriage.

Their marriage was planned for 22 December 1956, but these plans were nearly derailed when Oliver was arrested on charges of Treason on 6 December. Luckily, he was granted bail and the marriage went ahead as planned.

The couple had complementary personalities. Oliver was quiet and thoughtful, often to the point of reticence, although as his later political career shows, he was capable of assertive leadership. By contrast, Adelaide had a commanding personality and laughed a lot. She enjoyed wearing bold, even flamboyant, clothes that amplified her personality and presence.

Women in the anti-apartheid struggle

Challenging the specific impacts of apartheid on women was core to Adelaide’s campaigning. From the 1920s onwards, the South African trade union movement had increased the involvement of African women in political organising. But from the 1950s, women increasingly came to play a key role in most aspects of the anti-apartheid movement. On 9 August 1956, Adelaide took part along with 20,000 other women in the march on the Union Building in Pretoria against the extension of the pass laws to African women.

Image: Jurgen Schadeberg – Early July 1952: A group of ANC women, having been briefed by the Defiance Campaign leaders, are ready to defy (Courtesy of Claudia Schadeberg www.jurgenschadeberg.com)

The protest was organised by the Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW). Oliver Tambo drew two lessons from women’s anti-apartheid campaigning in this period. First, he came to understand the importance for the ANC of organising around the impact of apartheid on people’s everyday lives. Second, he challenged men within the movement to support demands for women’s equality, including sharing caring commitments within the home and family so that women could independently engage in political work.

26th August 1952, a group of 29 women from the ANC Women’s League march into Gersmiston Township. Extreme left of picture A. Naidoo, Amina Asmal, Miriam Cachalia (dark glasses), Amina Cachalia, Viginia Thoko Ngomo, Ida Mntwana. Image: Jurgen Schadeberg – Six Decades of Jazz – (Courtesy of Claudia Schadeberg www.jurgenschadeberg.com)

The Tambos in exile

In January 1957, Oliver Tambo was one of the earliest Treason Triallists to have the charges against them dropped. In contrast, the trial against some defendants, including Mandela and Sisulu, continued until 1961. As early as April 1958, Oliver Tambo was instructed by Chief Albert Luthuli that, if the ANC was banned, the National Executive had decided he should be sent abroad to serve as an ambassador for the organisation. At that point, Adelaide was reluctant to follow this instruction, as it cut across her commitment to care for elderly relatives. However, when the ANC was banned in March 1960, she duly followed Oliver into exile. They and their family would live outside South Africa for the next 30 years.

Portrait of Adelaide Tambo (courtesy and copyright Oliver & Adelaide Tambo Foundation/ Tambo Family Archive)

The family settled in London (although Oliver would later spend extended periods of time at the ANC’s headquarters in Lusaka and travelling the world on ANC business). Initially, they lived in rented accommodation in Highgate, supported by Christian Action and the International Defence & Aid Fund (IDAF). Later they moved to 51 Alexandra Park Road in Muswell Hill, where IDAF continued to pay their mortgage.

Soon after their arrival in London, Adelaide returned to work as a nurse, often working double-shifts to support her family. For many years she worked at north London’s Whittington Hospital, as a district nurse, spent time for Haringey council as a care worker with young people, and later ran a care home for the elderly in the area.

'Ma' Tambo and the politics of care

From the early days of their time in London, Adelaide played a key role in helping South African opposition members adjust to exile in the UK and looking out for their welfare. She was famous for attending and helping to organise marriages and funerals within the South African exile community, extending her care not just to ANC members and their allies, but also to supporters of the Pan Africanist Congress and other organisations.

Image: Adelaide Tambo (courtesy and copyright Oliver & Adelaide Tambo Foundation/ Tambo Family Archive )

In October 1987, she challenged fellow ANC members against unproductive arguments between the ANC and PAC over their history and politics. Despite her long political commitment to the ANC, Adelaide tended to approach problems within the exile community not in terms of political rhetoric, but by focusing on practical solutions. After the Soweto Uprising in 1976, she was active in raising financial support for the families of young people who were forced into exile. At her funeral in 2007, Mandela described Ma Tambo as “a mother to the liberation movement in exile”. She often made space in her home to accommodate recently arrived exiles, particularly unaccompanied young activists.

In addition to her paid and unpaid care work, Adelaide continued to be involved in political and diplomatic work for the ANC. During her time in exile, Ma Tambo became a founding member of Afro-Asian Solidarity Movement and the Pan-African Women’s Organisation (PAWO). In London she made it her duty to get to know diplomats from African and Asian countries and raise the profile of the ANC amongst them. She threw lavish parties at her home to build these networks. At the same time, she was active in the ANC Women’s League and was not afraid of using her influence there to challenge decisions made by the men in the ANC’s leadership.

She also played a key role in ensuring that ANC women made connections with feminist organisations in London and internationally. She was a close friend of Selma James, one of the co-founders of the international Wages for Housework Campaign, which sought to make women’s unwaged care work visible and valued.

Women played a key role in every aspect of the anti-apartheid struggle – they organised in their unions, churches, and communities, they led protests, and they fought in the armed struggle.

Women played a key role in every aspect of the anti-apartheid struggle – they organised in their unions, churches, and communities, they led protests, and they fought in the armed struggle.

However, as Adelaide Tambo’s personal and political life shows they also organised and supplied care for members of the liberation movements and their families.

Too often women’s care work is overlooked or undervalued. But it was essential to the survival of the anti-apartheid movement. Remembering the political contribution of this care work is not only important for how we understand the role of women in the anti-apartheid struggle, but also crucial to fighting against oppression and inequality today. Without valuing care for the people we campaign alongside, we cannot hope to create a more just world with care for each other and care for the planet at its centre.

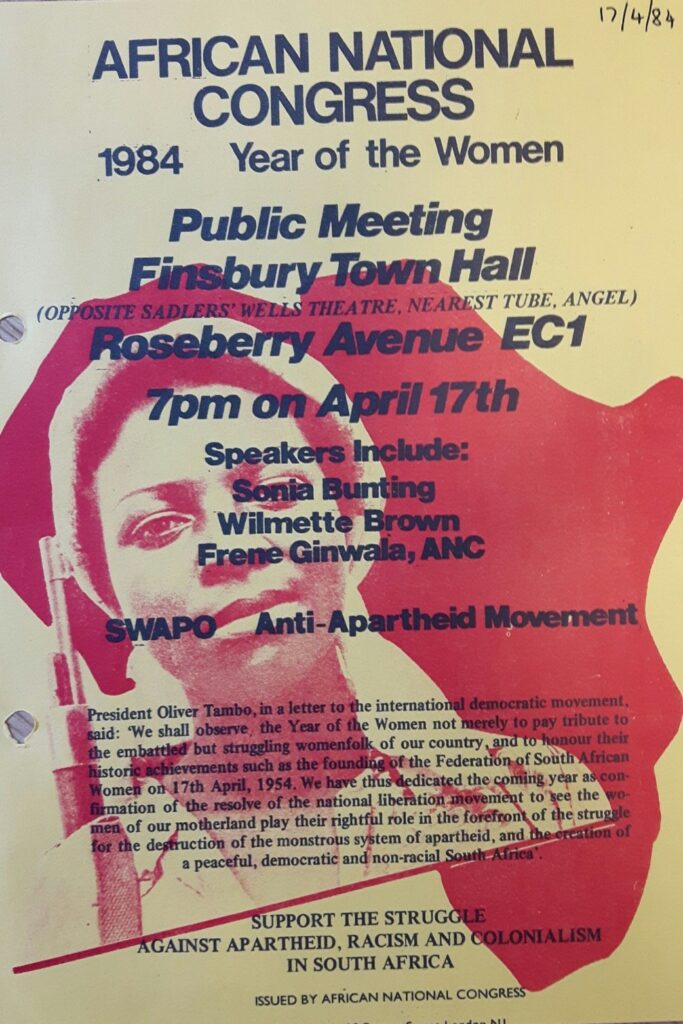

Image: Leaflet for ANC ‘Year of the Women’ public meeting in London, 1984 (Image from the Steve Kitson Archive at the Bishopsgate Institute).