City Group Singers anti-apartheid choir sings outside the South African Embassy in London (image: Jonathan Kempster NUJ)

On 21 March 1960, 69 unarmed anti-apartheid protesters were shot by the police in Sharpeville. In the days after the Sharpeville Massacre, the South African government arrested thousands of anti-apartheid activists and banned the African National Congress (ANC) and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). This meant that the two leading anti-apartheid organisations in South Africa could no longer organise legal, public protests. They were forced to work in secret. Without the ability to organise openly, both organisations changed their strategy and adopted armed struggle against the apartheid regime. Over the next few years, many of the movement’s leaders, like Nelson Mandela, were arrested and given to long prison sentences. In the early 1960s, reflecting these political changes, the nature of anti-apartheid songs also changed. Some of the songs from this period are sadder reflections on the violence and repression of the apartheid regime. But other songs were intended to mobilize support for the armed struggle.

A key song from this period is Thina Siswe. Like many popular anti-apartheid songs, Thina Siswe has no identifiable author and was probably the result of collective improvisation, with the lyrics changing over time. This song is a sombre lament. It doesn’t mourn the deaths of individual anti-apartheid protesters but mourns the dispossession of the African people from their land by European colonists and the apartheid regime. Key lyrics from the song translate as “we are crying for our land, our land which has been taken by the whites; we as the black nation, we are crying for our land. We say, ‘can they leave our land alone?’

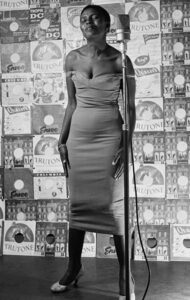

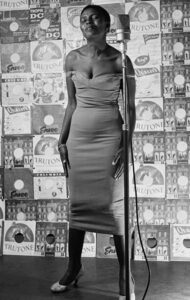

Miriam Makeba, 1955, This iconic photograph of Miriam by Jurgen Schadeberg was famously used as a cover for Drum Magazine in 1957. (Photographer: Jürgen Schadeberg – Six Decades of Jazz Image courtesy of Claudia Schadeberg, www.jurgenschadeberg.com)

As well as songs that developed on the streets, songs by popular South African musicians also reflected this change in the political climate. Some songs by these performers were taken up by the anti-apartheid movement and continued to be sung in protests and demonstrations. One example of this is the song Bahleli Bonke Etilongweni by Miriam Makeba. Makeba had become a popular performer in South Africa, and internationally, in the 1950s. At the time of the Sharpeville massacre, in which two members of her family were killed, she was living in New York. When her mother died later that year, she tried to return to South Africa for the funeral but found that the apartheid authorities had cancelled her passport. She was effectively forced into exile by the South African government. In response, she became a more vocal opponent of apartheid, and her songs became more clearly political. Bahleli Bonke Etilongweni (which means ‘our leaders are in jail’) is a slow, solemn and haunting song that was written in the mid-1960s and names Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu from the ANC and Robert Sobukwe of the PAC as leaders of the anti-apartheid movement who had been jailed. Over the next three decades, Miriam Makeba used her international fame to publicise the violence of apartheid and raise support for the anti-apartheid movement.

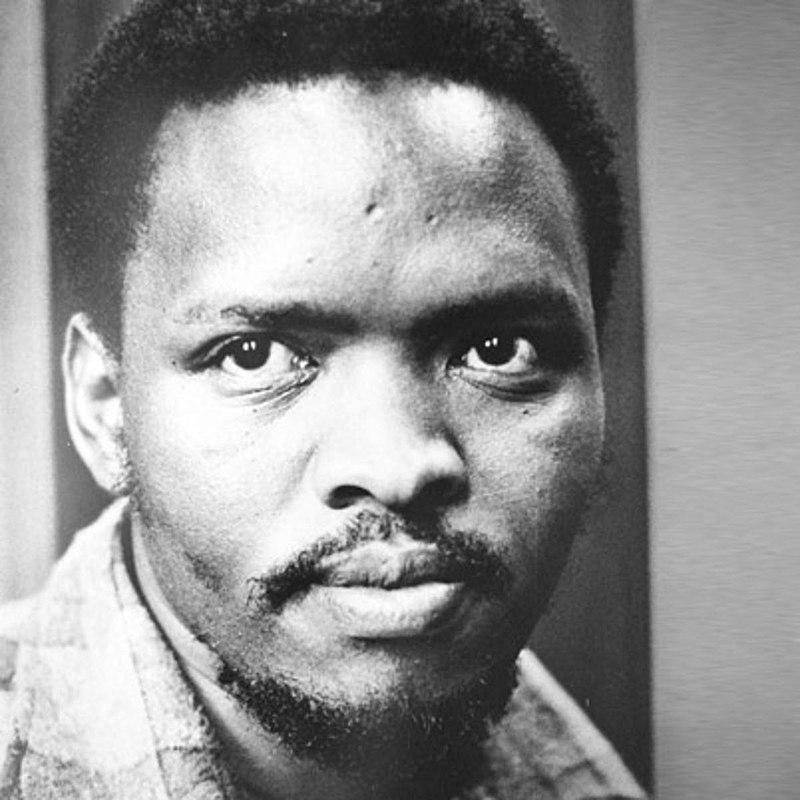

In addition to professional musicians like Miriam Makeba who became high profile anti-apartheid campaigners, there were also activists who used their musical talents to write songs for the movement. Vuyisili Mini was one of the most significant song writers to emerge from the anti-apartheid struggle. He had been a trade union organiser and local ANC leader since the early 1950s. In the 1960s, he was amongst the first people to join Umkhonto we Siswe, the armed wing of the ANC and South African Communist Party and joined the organisation’s regional High Command in the Eastern Cape province. He was arrested in May 1963, charged with 17 acts of sabotage, and involvement in the killing of a police informer. He was condemned to death and hanged by the apartheid regime in November 1964. Those who were in prison with him recall that he went to the gallows singing liberation songs, some of which he had written himself.

We want to highlight two of Vuyisili Mini’s songs that had a lasting legacy in the anti-apartheid movement. The first is a song of commitment to the ANC and its leaders, while the second is a song of defiance and challenge to the apartheid regime. Somlandela (We will follow), is a gospel song that was adapted for the anti-apartheid struggle. The name ‘Jesu’ in the original song was replaced by the name of the late ANC President Albert Luthuli. In contrast, Nants’ indod’ emnyama was originally sung as a threat to Prime Minister Verwoerd in the 1960s, but by the mid-1980s had been updated to threaten PW Botha, the current holder of that office. The title of the song translates as “Watch out Verwoerd, here come the Black people”. This song was sung almost as a taunt, it upset white supporters of apartheid, as it was a direct challenge to their authority (dressed up in what, at first, sounded like a cheerful, even fun, melody). Both songs use a call and response form, in which a soloist sings a line, which is then repeated by the other singers. The tone and syncopated rhythm of Nants emphasizes the threat and challenge contained in its lyrics. While, true to its gospel origins, Somlandela has a lighter sound and faster pace that encapsulates its more celebratory lyrics and intent.