Activity Against Apartheid: Britain

Jim Kerr of the rock band Simple Minds launched the Nelson Mandela Freedom March at a rally in Glasgow on 12 June 1988. Among the speakers at the rally were ANC President Oliver Tambo (furthest left), SWAPO leader Andimba Toivo ja Toivo (next to Tambo), Allan Boesak of the UDF (behind Kerr), Domingos Ginga of MPLA, Labour MPs Bernie Grant and Joan Lestor and the President and Chair of the AAM, Trevor Huddleston of the AAM and Bob Hughes MP. The Freedom March was part of the AAM’s Nelson Mandela: Freedom at 70 campaign. Image courtesy of the Anti-Apartheid Movement Archives.

Nelson Mandela was inaugurated as South Africa’s first democratically elected president in May 1994, bringing to an end a long struggle against apartheid. The struggle was led by South Africans, with support from people all over the world.

Britain had closer ties with apartheid South Africa than any other country. In the 1950s and 1960s it was South Africa’s biggest trading partner and foreign investor. Thousands of white Britons emigrated to South Africa and the two countries had close sporting and cultural links. Successive British governments refused to end these links. So the main focus of anti-apartheid campaigning in Britain was mobilise public opinion to isolate South Africa and end British support for apartheid.

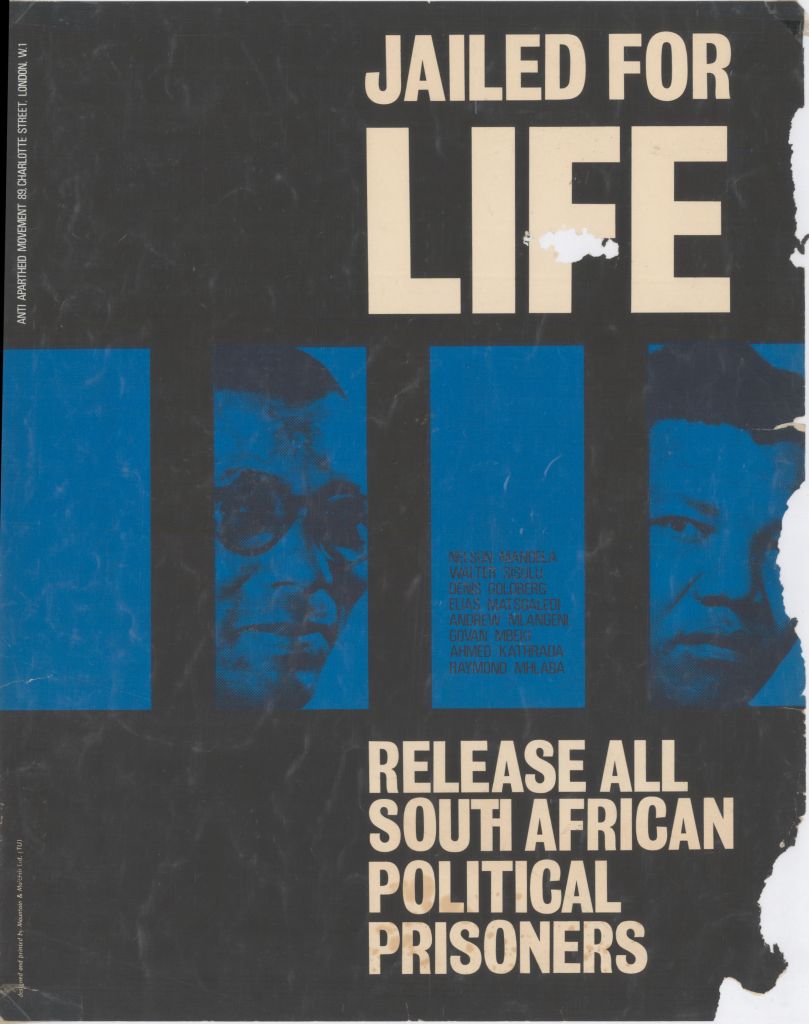

Poster about the results of the Rivonia Trial with the names of the defendants who were sentenced to life imprisonment. The Anti-Apartheid Movement began a campaign in November 1963 to save the lives of the Rivonia Trial defendants when it was widely feared that all would be convicted and hanged. There was an international campaign to save the defendants lives. The defendants were Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Denis Goldberg, Elias Matsoaledi, Andrew Mlangeni, Govan Mbeki, Ahmed Kathrada, Raymond Mhlaba and they were members of the African National Congress (ANC). Image credit: Liz Blum papers, Michigan State University Libraries Special Collections – used by permission of the Anti-Apartheid Movement Archives Committee.

Hundreds of thousands of people in Britain took part in anti-apartheid campaigns. By the 1980s the movement against apartheid had become the country’s biggest ever international solidarity movement, involving a huge range of people and organisations, including students, trade unionists, people of colour, faith groups, women’s organisations, community groups, members of all political parties and very many people without any political affiliation.

They called for an end to all links with apartheid South Africa: sanctions against trade and investment, a ban on arms sales, an end to all-white sports tours, and a cultural and academic boycott. They campaigned for the release of political prisoners, an end to the torture of detainees and clemency for those condemned to death, as well as sending undercover funds to pay for lawyers for those on trial for their political beliefs and for the living costs of the families of political prisoners.

Campaigning in Britain first got off the ground in 1959, when the President of the African National Congress, Chief Albert Luthuli, asked people all over the world to boycott South African products. South African political exiles and their British supporters set up the Boycott Movement. The move was overtaken by events at Sharpeville, where 69 unarmed people were shot dead by police at a protest against the pass laws organised by the Pan African Congress. The liberation movements, the African National Congress (ANC) and Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) were banned and they set up offices outside South Africa, including in London. The ANC’s first office was at 49 Rathbone Place in Camden, and in 1978 it moved to 28 Penton Street, the home of the CML.

The Boycott Movement was transformed into the Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM), which for the next 34 years, until the overthrow of apartheid, worked closely with the exiled liberation movements. The AAM and the International Defence and Aid Fund (IDAF) were the lead organisations among a spread of ad hoc groups, created to work on particular campaigns or represent special interest groups. IDAF worked undercover to support political prisoners and their families, and set up a research and publications unit which exposed what apartheid meant for black South Africans.

Anti-apartheid campaigners first big success was to help save the lives of Nelson Mandela and his co-accused in the Rivonia trial in 1964. Partly because of the international campaign by the World Campaign for the Release of South African Political Prisoners, set up by the AAM and IDAF, they escaped the death penalty and were sentenced to life imprisonment.

Then in 1969–70, a coalition of anti-apartheid organisations, including the AAM, Stop the Seventy Tour, the West Indian Campaign against Apartheid Cricket and the more establishment Fair Cricket Campaign, forced the cancellation of the all-white Springbok cricket tour. From then on, South Africa was excluded from every major world sporting federation.

In the 1970s students took the lead in anti-apartheid campaigning, demanding that their universities sell investments in British companies that operated in South Africa. A network of students, set up by the National Union of Students and the AAM, raised funds for the Southern African liberation movements and set up scholarships for students from Southern Africa.

After the uprising by students in Soweto in 1976 and the murder of black consciousness leader Steve Biko the following year, Britain dropped its opposition to any sanctions against South Africa in the UN Security Council and voted for a mandatory UN arms ban against South Africa. This followed years of campaigning for a British and UN arms embargo.

In the 1980s, in spite of visceral opposition from Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, British public opinion called for sanctions against South Africa. Beginning with a 50,000-strong demonstration against South African Prime Minister P W Botha’s visit to London in 1984, the AAM mounted some of the biggest demonstrations ever seen on the streets of London, Glasgow and Cardiff. Many British companies, including Barclays Bank, closed down their operations in South Africa.

From 1978, when Prime Minister James Callaghan called for Nelson Mandela’s release on his 60th birthday, the campaign for freedom for Mandela mushroomed, culminating in the 1988 ‘Nelson Mandela: Freedom at 70’ campaign. Seventy-two thousand people attended a birthday tribute concert at Wembley Stadium, televised in 63 countries and watched by millions of viewers all over the world. Meanwhile City of London Anti-Apartheid Group mounted a non-stop 24-hour demonstration outside South Africa House in London demanding Mandela’s release.

Anti-apartheid campaigners in Britain added to the pressure on the apartheid government from South Africans struggling for their freedom, which led to the lifting of the bans on the liberation movements and the release of Mandela in 1990. During the negotiations over the next four years, they argued for free and fair one-person-one-vote elections in a unitary South Africa.

The anti-apartheid movement in Britain was unique as a campaign that saw itself as part of a wider struggle in which the peoples of Southern Africa were the main protagonists. It rejected the paternalism that underlay earlier British movements like the campaign for the abolition of the slave trade and which still informs much of white attitudes to Africa today.