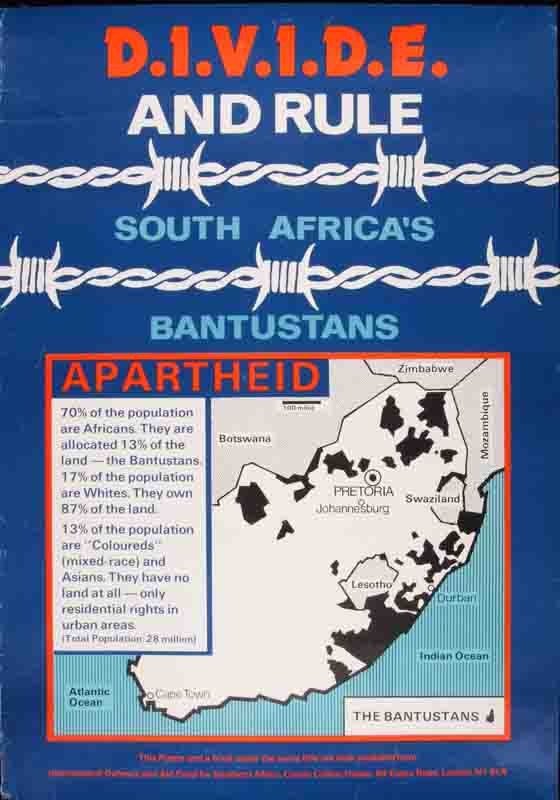

Apartheid (which means ‘apartness’ in Afrikaans) was a system of entrenched racial segregation. It was the law of the land in South Africa from 1948 to 1994.

The roots of apartheid can be found in Dutch and British colonialism. The Dutch East India Company established the first European settlement in southern Africa in 1652 at Table Bay (now Cape Town). The majority of these early settlers were farmers. They seized land from indigenous Africans and established a system of slavery so they could grow crops and raise livestock on a bigger scale. These early Dutch speaking settlers developed a distinct language known as Afrikaans and were often referred to as Afrikaners or Boers (farmers).

Britain first took control of the region in 1795, later establishing the Cape of Good Hope Colony. With the imposition of British rule and laws, around 13,000 Afrikaners left the settlement in the 1830s – embarking on what would become known as ‘The Great Trek’. This resulted in the establishment of the independent Boer Republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State in the interior of South Africa, far away from the Cape Colony. While the Dutch and British were colonial rivals, the laws and customs they enacted were all based around the exploitation of the indigenous African population. This effectively lay the groundwork for apartheid in the mid-twentieth century. The system of apartheid began in May 1948, when the National Party (NP) came to power in a narrow election victory. The NP represented the interests of the white Afrikaans speaking population.