September 1985: One of the many funerals during the State of Emergency of the mid-80s. Credit: Sechaba, official publication of the African National Congress, Sep. 1985 - JSTOR Primary Sources 09-01-1985 . Contributed by: African National Congress (Lusaka, Zambia).

Activity Against Apartheid: South Africa

For centuries, the people of South Africa have struggled to build a society founded on justice and equality. That fight for freedom has taken many forms, but few moments capture the spirit of its long struggle more than the events that occurred in the late 19th and early 20th century.

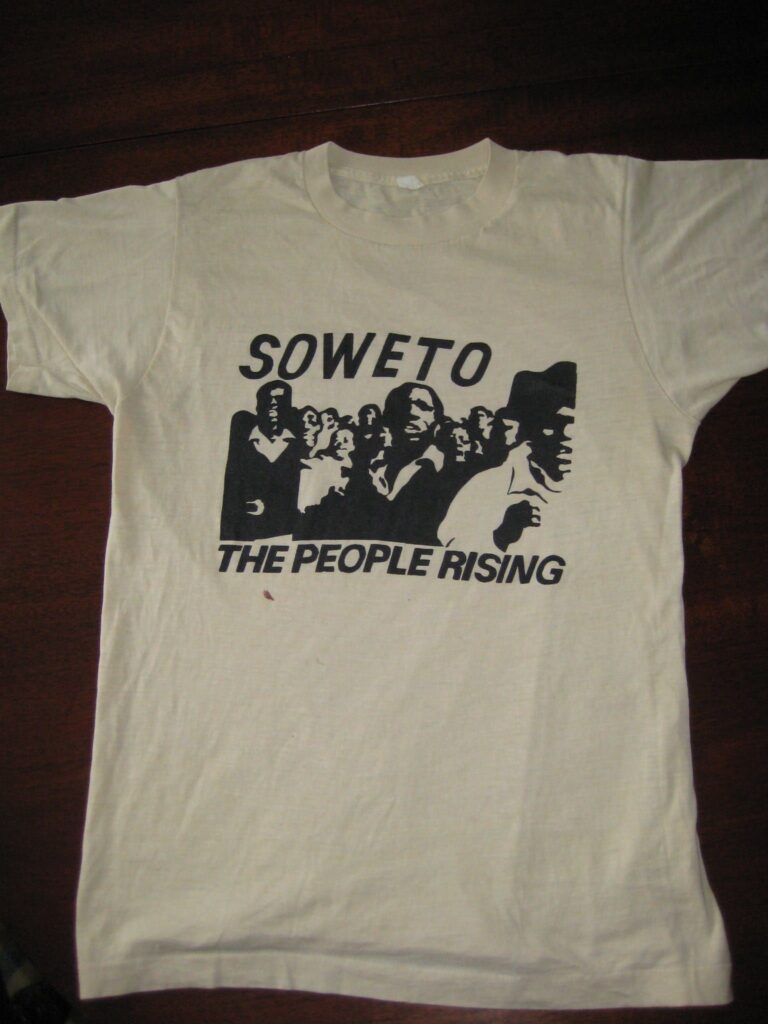

This white T-shirt about the Soweto uprising that started on June 16, 1976 has a black and white drawing on the front of many young people marching forward. Image credit: Private collection of David Massey – Used by permission of former members of the Boston Coalition for the Liberation of Southern Africa.

From the formation of the South African Native Congress (SANC) in 1912, the resistance to the Colour Bar in 1909, through to the declaraion of the Freedom Charter and the formation of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC) in 1959, the struggle was characterised by crucial moments which left a mark on this intense battle against racial oppression and apartheid.

And while it would take another 30 years of sacrifice and activism before true freedom was achieved, the major turning point came in March 1960 when 69 peaceful protestors were killed in Sharpeville.

Finally, in 1994, Nelson Mandela became president of a newly democratic South Africa after 27 years in prison. These momentous events make up just a few chapters in one of history’s most inspiring epics of freedom; the fight for justice in South Africa.

1909 – Resistance to the Colour Bar

After the Anglo-Boer War of 1988 to 1902, it became apparent that the closer relations between the two English Colonies of Natal and the Cape, as well as Boer Republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, would mean that the exploitation, land dispossession and social oppression of the native Africans, ‘Coloureds’ and Indians would continue in light of the earlier efforts of the Wars of Resistance led by the likes of Chief Moshoeshoe, Sekhukhune and others.

A deputation of leaders of the Africans, who were against the Colour Bar Clause proposed by the South African Parliament, was sent to England but was unsuccessful in convincing the British Parlianment not to support the adoption of the Clause. The passing of the clause by the new Act of the Union of South Africa would mean that the Africans would continue to be disenfranchised (for those who had the franchise in the Eastern Cape) and to lose their lands on an even larger scale in a dispossession drive.

January 1912 formation of the South African Native Congress (SANC)

A Conference was called in Bloemfontein at which a broad range of leaders of the African community from across the country formed a new organisation, whose purpose was to organise resistance to the Colour Bar and its devastating manifestations. On the same day, a leadership spearheaded by the Reverend John Langalibalele Dube (President) and Mr. Sol Plaatjie (Secretary-General) was elected. The name of this new bulwark against colonial rule was called the South African Native Congress (SANC), the predecessor to the modern-day African National Congress (ANC).

Kadali and the Workers Movement boost the resistance movement

Efforts to resist the manifestations of the actions of the repressive and exploitative collaboration between capital and the political elite, were given a boost in 1919 with the formation of the Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU), led by Clements Kadali.

The Freedom Charter

In June 1955 a gathering called the Congress of The People (C.O.P), which was comprised of the SANC, the South African Indian Congress, the South African Coloured People’s Congress and the South African Congress of Democrats, adopted the Freedom Charter in Kliptown, Johannesburg. According to the C.O.P, the Charter was a Bill of Rights statement for all South Africans, irrespective of race, colour or creed. It set out a vision for a multi-racial South Africa in the post-apartheid era.

The Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) is formed

A new dimension to the internal Anti-Apartheid Movement was ushered in on the 6th of April 1959 with the formation of the PAC in Orlando East, Soweto. Many of the founding leaders of the PAC, such as its first president Robert Mangaliso Sobokwe, had been founder members of the ANC Youth League. The PAC worried that the multi-racialism of the Freedom Charter accepted the racial divisions built into the apartheid system.

The Pan Africanists argued that multi-racialism inherently recognised race, whereas the PAC said race would not be significant in a free Azania (the PAC’s preferred name for South Africa). Sobukwe proclaimed that there was “only one race, the human race” and that “multi-racialism was racism multiplied”. The PAC was the first to introduce the term ‘non-racialism’, as opposed to mutli-racialism, into the South African political scene.

March 1960 – The Turning Point

Towards the end of 1959, both the ANC and the PAC announced campaigns geared towards the resistance of the government’s Pass System. In a peaceful protest called for the 21st of March 1960, the PAC called on all Africans to march to the closest police station and avail themselves for arrest on the basis that they were not carrying their passes. In Sharpeville, Johannesburg the police responded very harshly to a gathering in front of the police station with the killing of 61 protesters, most of whom were shot from the back. The repurcussions of this act of brutality reverberated throughout the whole world, leading to the germination of the African and the international Anti-Apartheid Solidarity Movement, as well as the adoption of armed resistance as one of the forms of struggle by both the ANC and PAC.

It was also during this period that South Africa was expelled from various international institutions including international sports bodies, the Commonwealth and others. A crackdown on the leadership of the ANC and PAC resulted in mass arrests across the country and ultimately both were outlawed on the 8th of April 1960. It was from this point onwards that both parties also begun sending large numbers of people out of the country with the intention being to galvanise the world to resist the apartheid state, as well as to gather resources and organise the military efforts of Umkhonto We Sizwe (MK), and Poqo, the military wings of the ANC and PAC, respectively.

1970 to 1994 -the struggle gains momentum

The independence of Mozambique in 1974 inspired the first generation of South African students who adhered to the Black Consciousness ideology to organise victory rallies across the country. These actions gave impetus to the re-politicisation of young people, with the result manifesting itself with protests by school students against the government’s instructions for students to study in Afrikaans and English as mediums of instruction. The state’s reaction to these actions led to the tragic events starting on the 16th June 1976.

From 1976, the internal resistance movement gained a high level of momentum, and together with the international solidarity movement led to increased pressure being put on the South African apartheid state.

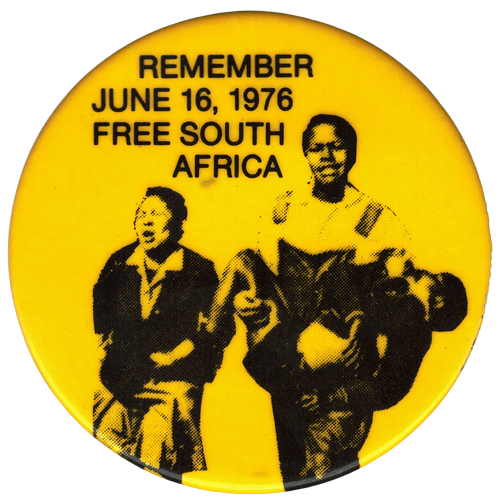

Round, yellow anti-apartheid button with a black image of a well-known photograph by Sam Nzima of Mbuyisa Makhubu carrying the body of Hector Pieterson, the first child to be shot dead by police in Soweto on June 16, 1976. Pieterson’s sister Antionette Sithole runs alonside. Credit: South African Student Union (SASU), published courtesy of the collection of William Oliver.

June 16 Soweto Uprising – The Soweto Uprising of 1976 was a pivotal event in the South African liberation struggle against apartheid. It began as a student protest against the government’s policy of compulsory education in Afrikaans, the language of the oppressor, rather than the students’ native languages. On June 16, thousands of students from Soweto, a township near Johannesburg, took to the streets, demanding quality education and an end to apartheid.

The protest was met with brutal force from the police, leading to clashes and the tragic loss of innocent lives, including that of 13-year-old Hector Pieterson, whose iconic photograph became a symbol of the uprising. The Soweto Uprising galvanized widespread resistance against apartheid, attracting international attention and inspiring further acts of defiance. It marked a turning point in the liberation struggle as it revealed the determination and courage of the youth in fighting against oppression.

The events of 1976 laid the foundation for future resistance movements, energized the anti-apartheid movement, and ultimately contributed to the dismantling of apartheid in South Africa.

The People’s Resistance and the State of Emergency of the mid-1980s

The mid-1980s in South Africa were marked by a state of emergency declared by the apartheid government in response to widespread protests and escalating resistance against its oppressive policies. The state of emergency, implemented between 1985 and 1986, granted the government extensive powers to suppress dissent, suspend civil liberties, and impose curfews.

The primary objective was to quell the growing anti-apartheid movement and maintain control over the black majority. The state responded with increased repression, deploying security forces to crack down on protests, conducting mass arrests, and implementing censorship measures to stifle opposition voices. The state of emergency resulted in widespread human rights abuses, including torture, detention without trial, and extrajudicial killings. However, despite the government’s efforts to suppress resistance, the state of emergency also galvanized the anti-apartheid movement, further mobilizing activists, trade unions, and international solidarity.

The resilience and determination of the South African people during this period laid the groundwork for the eventual end of apartheid and the establishment of a democratic South Africa. The effects of economic sanctions also made a tremendous impact on the economy while the internal Mass Democratic Movement (MDM) organised resistance to apartheid on levels that had never been attained before.

Towards the dispensation

The period towards the end of apartheid in South Africa, from the release of Walter Sisulu in 1989 to 1994, was marked by both significant political progress and tragic instances of political violence. Walter Sisulu’s release in October 1989, after spending 26 years in prison, symbolized a shifting political landscape and ignited renewed hope for the anti-apartheid movement.

Sisulu’s release, alongside the freeing of other political prisoners, including Zephaniah Mothopeng of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), was a significant step towards the unbanning of political organizations.

In 1990, de Klerk announced the unbanning of the ANC, PAC, and other anti-apartheid organizations that had been banned for decades. This pivotal decision opened up avenues for political engagement and dialogue, allowing these organizations to operate openly, mobilize their supporters, and participate in the negotiation process.

However, the path towards freedom was not without obstacles. During this period, South Africa experienced outbreaks of political violence, particularly in townships and regions that were hotspots of anti-apartheid resistance. Rivalries between political factions, including ANC and IFP, led to clashes resulting in a significant loss of life.

The human and economic costs of the efforts were very high but ultimately these actions bore fruit with the end of apartheid and the election of the first democratically-elected government of South Africa in 1994, led by the ANC’s Nelson Rholihlahla Mandela as President.