LGBT activists in the anti-apartheid struggle

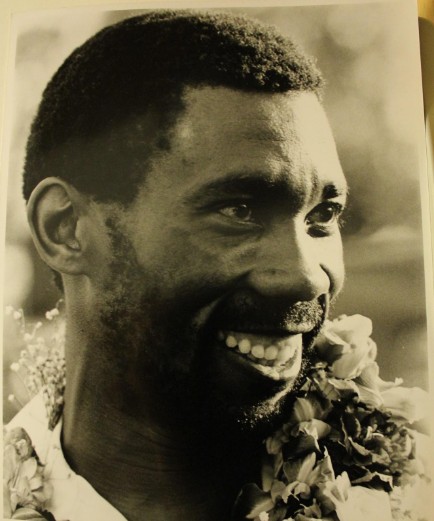

Image: Simon Nkoli attending a rally celebrating his release from jail in London - Photographer: Gordon Rainsford.

After the end of apartheid, South Africa became the first country in the world to guarantee freedom from discrimination on the grounds of sexuality as a constitutional right. The ‘equality clause’ in the 1996 South African Constitution was an attempt to overcome the legal inequalities (based on race and ethnicity) that had shaped South African society throughout the colonial and apartheid eras.

However, the specific inclusion of protection against discrimination based on sexuality was a direct response to the visible role that some LGBT people had played in the struggle against apartheid in the 1980s. As LGBT people became more visible in the anti-apartheid struggle, they organised around the slogan “no liberation without gay liberation” (using terminology that made sense at the time). They argued that it was not enough to opposed racial inequalities in South Africa, but that a post-apartheid nation had to oppose all forms of social and legal inequalities.

Here we tell the story of two gay anti-apartheid activists, and the LGBT groups they worked with, who helped raise the visibility of LGBT rights in South Africa during the last years of the apartheid system. We focus on the stories of Simon Nkoli and Ivan Toms, but there are many other important LGBT activists who campaigned with them. They include Zackie Achmat, Sheila Lapinsky, Alfred Machela, Bev Ditsie, Edwin Cameron and others.

Simon Nkoli: black gay leader

Simon Nkoli attending a rally celebrating his release from jail in London (Photographer: Gordon Rainsford)

Simon Nkoli was part of the generation of South African activists who came into the anti-apartheid struggle during the 1976 Soweto school students’ uprising. Simon was 15 at the time of the Soweto Uprising and was detained by the security police for three months as a result of his involvement in the protests. When the Congress of South African Students (COSAS) was formed in 1979 to organise Black students in secondary schools and technical colleges, Simon became an active member. When he became the Regional Secretary for COSAS in the Transvaal region in 1981, some of his fellow activists questioned whether it was right for a gay man to hold that leadership position. But Simon stayed in his leadership role.

In 1983, Simon joined the (predominantly white) Gay Association of South Africa (GASA) and, through them, formed the ‘Saturday Group’ which was one of the first Black gay organisations in Africa. Until then, the few Black members of GASA had had to travel to white areas of Johannesburg to attend gay events. In contrast, the Saturday Group organised activities for its members in the black townships where they lived. This was an important attempt to make black LGBT people more visible within their own communities.

COSAS played a key role in forming the United Democratic Front (UDF) as a mass movement against apartheid in 1983. The UDF was an alliance of community groups, student groups and trade unions, all united in their opposition to apartheid. Simon quickly became active in the United Democratic Front. In 1984 he spoke at rallies in support of the rent boycotts in the townships. He was later arrested and charged with treason – one of the defendants in the Delmas Treason Trial alongside high profile activists such as Popo Molefe and Patrick Lekota. He refused to hide his sexuality or his history of gay activism during the trial (at first, to the discomfort of some of his co-defendants).

The Delmas Treason Trial was one of the largest and most significant trials of anti-apartheid leaders in South Africa during the 1980s. As a result, the 23 defendants in the trial received a lot of support and solidarity from the international anti-apartheid movement. Because Simon Nkoli stood trial as a proud Black gay man, many LGBT groups and individuals around the world became involved in anti-apartheid campaigning. In December 1986, while he was still in prison, Simon received over 150 Christmas cards from gay anti-apartheid campaigners in Britain and the Netherlands. This level of support helped persuade his co-accused that Simon was not putting them all at risk during the trial. However, Simon was also adamant that international support just for himself, making him a special cause due to his sexuality, was not helpful and could do more harm than good – he wanted the international gay community to stand in solidarity with all the defendants. He was eventually found not guilty in 1988, released from jail and returned to anti-apartheid and LGBT campaigning.

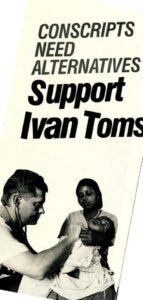

Ivan Toms: white gay war resistor

“Conscripts Need Alternatives: Support Ivan Toms” (c. 1988). End Conscription Campaign. 7.

Ivan Toms was a white doctor who lived in Cape Town. During the apartheid era, South Africa had compulsory military national service for all white men. He had served as a medic in the South African Defence Force in Namibia during his national service. When his military service ended, Ivan set up a free clinic in the Crossroads squatter camp near Cape Town. Having seen the army being used to violently evict the residents of Crossroad in 1983, Ivan helped found the End Conscription Campaign to oppose compulsory military service. At this time, he publicly declared that, in line with his Christian faith, he would refuse to serve new reservist duties in the South African army. In 1988 he was jailed for 9 months for his stance.

The experiences of both Ivan Toms and Simon Nkoli suggest how people’s lived experience inspired them to actively oppose apartheid. Both were supporters of the ANC-aligned United Democratic Front, but their understandings of the problem of apartheid and how to overcome it cannot be reduced to support for the demands set out in the ANC’s Freedom Charter. For both Simon and Ivan, their sexuality and their religious faith played a significant role in shaping their political activism.

They were not alone in this. The sociologist Daniel Conway has shown that a disproportionate number of white South African men who refused to serve in the apartheid army were gay – precisely because their sexuality brought them into conflict with the very violent and authoritarian ways white men were expected to act in apartheid South Africa.

When Ivan Toms refused to report for his reservist duties in the army, he was subjected to a torrent of homophobic harassment and abuse. Ivan was clear that he wanted to link his experience of oppression as a gay man to his decision to refuse to serve in the army, but the End Conscription Campaign were nervous of making this link too publicly, fearing it might undermine the broad-based support they were building.

In the end, Toms was persuaded to downplay (but not completely hide) his sexuality during his trial. This didn’t stop LGBT and anti-apartheid activists around the world from supporting him and campaigning for his freedom.

No liberation without gay liberation

The international campaigns supporting Simon Nkoli and Ivan Toms helped add legitimacy to the network of lesbian and gay activist groups in South Africa which were beginning to organise non-racially and explicitly align themselves with the mass democratic movement against apartheid.

Simon Nkoli’s anti-apartheid activism began before his involvement in gay activism and community building. When he first joined the Gay Association of South Africa, Simon experienced the racist attitudes of white members of GASA towards himself and the few other Black gay people who attended GASA events. This provoked him to rethink how his sexuality shaped his wider political beliefs and his opposition to apartheid. During his treason trial, GASA refused to support or defend Simon because he had not been arrested for crimes related to his sexuality. He challenged their attempt to separate gay rights from anti-racism and the anti-apartheid struggle. Simon championed the idea that there could be “no liberation without gay liberation”.

After his release from prison, Simon Nkoli formed GLOW – the Gay and Lesbian Organisation of the Witwatersrand. GLOW was a black-majority LGBT group that organised around Johannesburg. In Cape Town, Ivan Toms was involved with the Organisation of Lesbian & Gay Activists (OLGA). Both GLOW and OLGA were LGBT organisations that affiliated to the United Democratic Front. By doing this, they made the campaign for LGBT rights part of the anti-apartheid struggle and argued that LGBT rights couldn’t be achieved in South Africa without overthrowing apartheid.

“Speaking for ourselves” t-shirt produced by GLOW – the Gay and Lesbian Organisation of the Witwatersrand

(image: Gavin Brown)

Under the leadership of Simon Nkoli and Bev Ditsie, GLOW organised the first LGBT pride march in South Africa in 1990. In the speech that he made at the start of the pride march in Johannesburg that year, Simon said,

this is what I say to my comrades in the struggle who ask me why I waste time fighting for moffies [South African slang for femme gay men]. And this is what I say to white gay men or women who ask me why I spend so much time talking about apartheid, when I should be fighting for gay rights. I am Black and I am gay. I cannot separate the two parts of me into two secondary or primary struggles. They will be all one struggle.

During his trial, Simon Nkoli found out that he was HIV+. In addition to his anti-apartheid and gay rights campaigning, he was also a key figure in campaigning for the needs of people living with HIV in South Africa. Simon died of an AIDS-related illness in 1998, before effective anti-retroviral treatments for HIV became widely available in South Africa.

At his funeral, echoing the anti-apartheid slogan ‘Amandla! Ngawethu!’ (Power to the people!), it was said that “Simon gave power to the people, and he gave power especially to lesbians and gays”.

After the end of apartheid, South Africa was at the forefront of extending LGBT rights around the world. In addition to the constitutional protections against discrimination based on sexuality, South Africa was the fifth country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage in 2005. These legal equalities would not have been achieved without the high-profile activism of people like Simon Nkoli and Ivan Toms, who refused to separate gay liberation from the struggle against apartheid. They started to change attitudes towards LGBT people in South Africa. However, despite the positive changes in South African law over the last 25 years, there are still high levels of homophobic and transphobic violence in South Africa. The struggle for LGBT rights is not over. Simon Nkoli showed that freedom and justice for LGBT people had to be based on meeting the needs of the poorest and most marginalised sections of the LGBT community, not its most privileged. That is an important lesson that we should continue to learn from in the UK and around the world.