Activity Against Apartheid: International

June 1979: David Sibeko (Centre), Permanent Representative of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC) at the United Nations (UN), holds a press conference at UN Headquarters. Seated next to him are the then London-based Barney Desai (left), Chairman of the Second Consultative Conference of PAC, and Mike Morgan (right), a deserter from the South African Defence Force (SADF). Credit: UN Photo/Yutaka Nagata

Resistance to the brutality of Apartheid was led by the country’s Black subjugated communities. Indian and Coloured people, who also faced racial discrimination as a result of the regime’s absurd racial stratification system, joined forces with their Black comrades in significant numbers to fight against the racist laws.

In addition, a considerable number of White South Africans were prepared to take action against the regime in support of the oppressed groups.

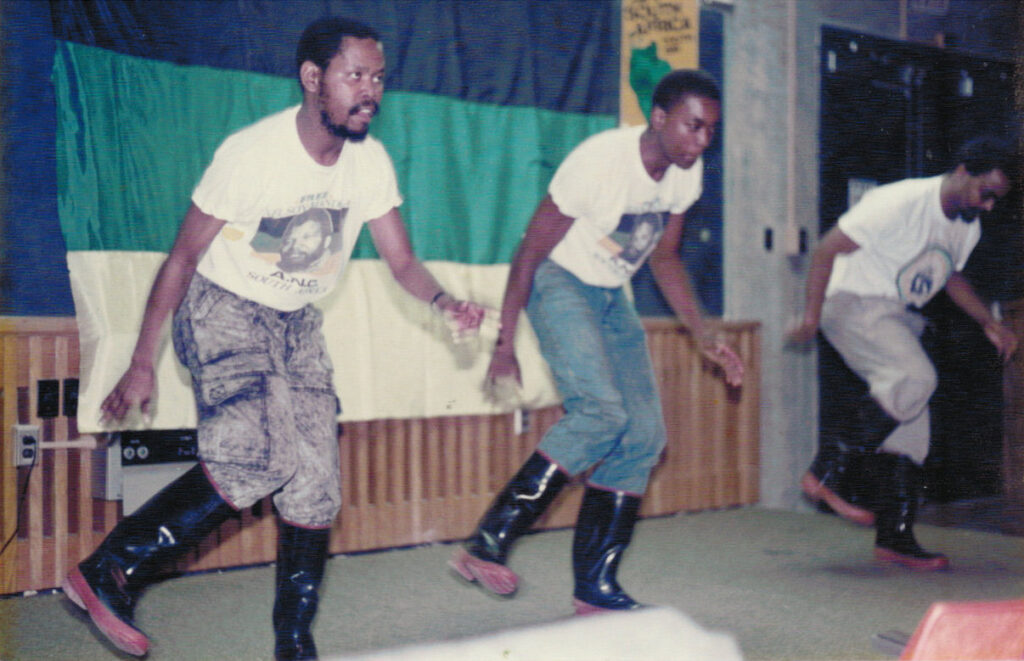

Sechaba, the African National Congress (ANC) cultural group performing at a gala cultural program to benefit and celebrate the sendoff of over five hundred boxes of books, school supplies and clothing to South African refugees at the Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College (SOMAFCO) in Tanzania at Gladfelter Hall, Temple University. Sechaba presented songs and dances of South African liberation. The program was sponsored by Friends of SOMAFCO, the Department of African-American Studies at Temple University, the Pan-African Community Education Program, and the Center for Black Culture and History. Image credit: used by permission of Friends of SOMAFCO.

The struggle for freedom in South Africa was by no means an easy process as the colonial domination by white European invaders/settlers throughout the African continent and globally was both ideological and physical. Afrikaners claimed that they ruled as a result of ‘divine intervention’. Having seized power, their sense of entitlement to land that did not belong to them and exploitation of its people became the framework of Apartheid.

Europe’s ruling classes perpetuated racist ideologies both at home and beyond. An unforeseen by-product of Britain’s link to South Africa, through the Boer War, was that many British citizens later played a part in shaping the Anti-Apartheid Movement.

The AAM attracted critics of the British Empire including trade unionists, anti-fascists, pacifists, student activists, teachers, writers and artists as well people from a variety of faiths. Over decades, their collective action gained momentum and inspired what can be described broadly as the international Movement Against Apartheid.

This wide topic cannot be explored fully within the parameters of this article. Instead, some of the key acts of international solidarity with the oppressed people of South Africa will be highlighted.

Gandhi’s visit to South Africa and his passive resistance campaign in India against British rule, led him to expose the plight of Indian South Africans. In 1946, India voted against white South Africa’s anti-Indian policies and banned trade with South Africa. In South Africa itself, Indian activists were then inspired by Gandhi to lead their own passive resistance campaign between 1946-1948. What is interesting is how this type of non-violent action was later adopted by Martin Luther King in America’s Civil Rights Movement.

In 1953, a delegation of South African activists took a big risk by being stowaways on a ship sailing to Europe. They continued their onward journey by train to Bucharest as delegates to the Fourth World Youth and Student Festival. Workers, trade unionists, artists, writers, students and many others from around the world gathered. They discussed strategies for winning freedom in their respective countries as well as offering solidarity to each other. This was an opportunity for the South Africans to tell others of the atrocities taking place in their country.

In both America and South Africa, there was arguably, an inevitable transition to violent methods being adopted in the fight for freedom, given the intractable position of consecutive racist US administrations and South Africa’s racist Nationalist government.

This shift was most clearly espoused by Malcolm X and the Black Panther Movement in America during the 1960s and in 1961 via the armed wing of the ANC with the creation of Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation) led by Nelson Mandela.

During Mandela’s and his co-defendants’ incarceration on Robben Island, it became essential for the ANC’s exiled community in London to work with the British Anti-Apartheid Movement to raise international awareness of Apartheid and demand change.

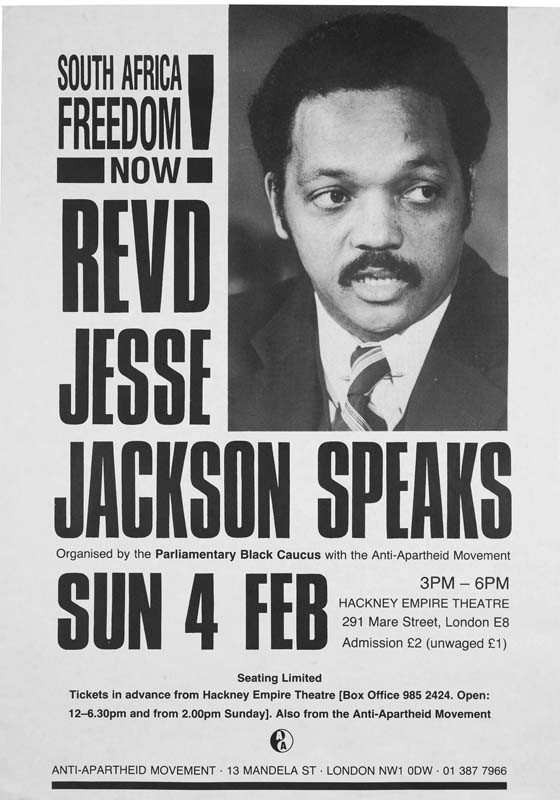

Poster advertising a meeting with a speech by Reverend Jesse Jackson at the Hackney Empire Theatre, London February 4, 1990, organized by the Parliamentary Black Caucus and the Anti-Apartheid Movement. Image credit: used by permission of the Anti-Apartheid Movement Archives Committee. copyright © AAM Archives Committee

Over the next thirty years several key figures from the Black Civil Rights Movement in America visited London and addressed Anti-Apartheid rallies as an act of solidarity with the disenfranchised people of South Africa. Angela Davis and Jesse Jackson are just two of those activists who supported the ANC liberation movement.

In 1984, Mary Manning, a shop worker at Dunnes Stores in Dublin followed the directives of her union by refusing to handle South African goods as a stand against Apartheid. She and shop steward, Karen Gearon, were suspended by management. In a huge act of solidarity, 10 of their colleagues went on strike in support of them. The strike continued until 1987 when the Irish government finally took a stand and banned the importing of South African goods.

Prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall, the former German Democratic Republic (GDR) offered international support by banning all trade with South Africa. Cuba provided practical support by deploying soldiers on the ground in the armed struggles against colonialism in various regions of Southern Africa as well as offering medical aid to activists.

There were huge international campaigns for sports boycotts against South Africa. The articulate, popular and charismatic boxing legend, Muhammad Ali, spoke out against Apartheid and in support of Black Civil Rights in America.

Over time, a call for artists to boycott South Africa and not be tempted by money to play at Sun City developed not just in Britain but across the world. When Hugh Masekela, was still a young boy, he was given his first trumpet by Archbishop Trevor Huddleston who was working in South Africa at the time. Both men became key figures, through their very different vocations, in the fight against Apartheid.

South African singer, Miriam Makeba, helped spread the word about Apartheid during her long international career and collaboration with actor Harry Belafonte who was and remains a strong opponent of racial injustice. Marlon Brando spoke out about Apartheid as early as the 1950s and almost forty years later starred in Euzhan Palcy’s film adaptation of Andre Brink’s book about South Africa ‘A Dry White Season’.

Perhaps the most commercially successful and politically impactful film on Apartheid, was Richard Attenborough’s ‘Cry Freedom’ 1987. It told the story of the brutal murder of the Black Consciousness leader, Steve Biko by the Apartheid regime and white journalist, Donald Woods’, determination to uncover the truth. The film changed public opinion worldwide, reflected in a rise in anti-apartheid activists and members across the globe.

The many musicians who joined Artists Against Apartheid helped to generate further pressure on South Africa to release Mandela and his comrades.

Meanwhile, the steadfast stalwarts in AAM continued to demand that the British government must end trade with South Africa. This message eventually travelled beyond Britain.

One of the most successful campaigns was achieved through the National Union of Students in Britain. Barclays Bank had established the monopoly on student accounts owing to the terms it offered. Students did not have big banks accounts but were strong in voice and action and their boycotting of Barclays Bank, owing to its dealings with South Africa, had a huge impact on public opinion. In turn, this worried global investors who feared that the increasing negative publicity might sully their own reputations. Once this particular campaign proved to be successful, large corporations grew ever more anxious over the impact on their banking with Barclays and soon started to pull-out. People the world over stood up against Apartheid but real change only came when big business and governments felt the pressure to pull-out of South Africa and economic sanctions were more widely applied.