How The Moth took flight

by Paul Herzberg

Header image shows a view of the Namibian border. Photograph Paul Herzberg, 2010.

I left South Africa at the age of twenty-three, having just returned from the Angolan Border War as a re-conscripted soldier. It was nineteen seventy-six. Five years earlier I had completed compulsory National Service. In the intervening period things had changed. South Africa was caught in a volatile period, much happening on its borders and within. Black Consciousness was exploding in the townships, the Portuguese were fleeing Angola and Soweto was in flames.

The war in which I had been involved was like no other. It was entirely secret. Soldiers were forced to pledge their silence to the Apartheid regime, who were desperate that word did not get out internationally, as to what was going on beyond the Namibian border. It is a silence many maintain to this day. Much of that war was so harrowing, thousands of ex-soldiers on both sides still suffer from post-traumatic-stress-disorder.

Angola borders Namibia, then, under occupation by South Africa, with its own liberation movement, SWAPO, in exile, operating from wherever it could, chiefly southern Angola. The white regime, fearing repercussions of a newly elected Marxist government in Angola and burgeoning Russian, Chinese and Cuban influence in the region, mustered one hundred thousand National Service and Civilian Force soldiers to the border. At the same time thousands of Cuban troops gathered to the north, uniting with local MPLA Angolan and SWAPO forces.

Parachute jump exercise by SADF training in Bloemfontein 1979. Courtesy Marius van Niekerk.

Hundreds of hot pursuit attacks were launched across the border into Angola. The first major strike, “Operation Savannah” brought the South Africans within twenty kilometres of Luanda, Angola’s capital city. Over the next thirteen years, thousands of Angolans and Namibians were slaughtered and many white and black South African troops. It was South Africa’s Vietnam and involved the superpowers, exerting covert influence. A grim legacy of that war is that Angola remains the most mine-ridden country in the world.

The 1989 battle of Cuito Cuanavale proved to be a major turning point and was the largest battle in Africa since WW2. The Angolan forces, boosted in numbers, hardware and military tactics by the Cubans, finally held their ground. While both sides claimed victory, within months, negotiations for Nelson Mandela’s release began, as did the groundwork for the dismantling of Apartheid.

Between 1948, when the white Nationalist government came into power in South Africa and the present day, there have been several waves of South Africans coming to live in, or flee to, the United Kingdom. Each has been characterised by developing events in the home country. When the ANC was banned after the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre, many people in the liberation movement fled. The diaspora was substantial: some went to Eastern Europe where they were welcomed by several communist regimes; others fled to various parts of Africa, like Zambia and Tanzania, and a significant portion came to the United Kingdom. The Anti-Apartheid movement flourished in London and across the UK, working with, inter alia, South African exiles like Peter Hain, and liberation leaders including Oliver Tambo. Other waves included young men refusing to serve in the SADF, or those, like me, who chose to no longer be available to the Apartheid army or live in a country where racial oppression was sanctioned by the state.

The Dead Wait and The Moth

The Moth is my fourth script exploring, in part, the South African military experience. In each case my aim was to make the themes universal in nature.

The Dead Wait, which preceded The Moth, was nominated for The Verity Bargate Award, first produced at The Market Theatre, South Africa. It was adapted for radio and produced by the BBC, ABC Australia and WDR, Germany and had its UK Premiere at the Royal Exchange, nominated for several Manchester Evening News awards. It was produced at the Park Theatre London, in 2013 in an updated version and re-published by Oberon Books.

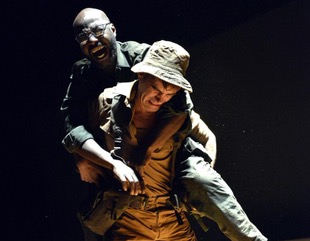

Sixteen years after my arrival in the UK, I began a conversation with a man on a train. Intrigued by my background he told me of an incident that had befallen his nephew as a young soldier in the border war. He had been on an Angolan mission and his unit had captured a wounded black freedom fighter. The unit commander had it in for the young soldier and suspecting their captive might be important, ordered the soldier to carry him on his back until they reached the border for interrogation. The freedom fighter whispered into the soldier’s ear as they moved through the bush — and in the mayhem, a bond began to grow. The commander, maddened by this unexpected course of events, finally ordered the soldier to execute the freedom fighter.

Maynard Eziashi as George, Austin Hardiman as Josh in the 2013 production of ‘The Dead Wait’ at The Park Theatre.

This image, one man on the back of another in the bush, ally and foe locked together, haunted me, and I felt that there were universal themes to explore in developing that anecdote into a play.

After The Dead Wait, I felt that I had explored this period of history enough. Then, during Covid lockdown, Elysium Theatre’s Artistic Director Jake Murray approached me and said that he was producing a series of short monologues for YouTube as a way of staying in touch with theatre. He asked if I had anything. I did — a partly written monologue that emerged from my discussions with former conscript, Angolan war veteran, film director and writer, Marius van Niekerk, during research for the film of The Dead Wait.

Marius told me several harrowing stories about that war. I used detail from some of them. One in particular, stayed with me, but there had been no place for it in the adapted screenplay: about a young white conscript battling PTSD, ordered to stand guard over a fatally wounded black freedom fighter, how the traumatised conscript responded to the agony of his ward, and how deeply affected he was by the consequences: a strange hiss escaping from the captive’s body after he took his last breath, and how, in the febrile mind of the conscript, it was as if the dead man’s soul was flowing into him. In responding to this extraordinary anecdote, I reimagined that escaping soul as a moth flying into the night sky — and the haunting sound of tiny, beating wings.

Again, I started to build a broader narrative to that story. Given my fifty-year absence from South Africa, and issues surrounding race and racism which are once again front and centre of global politics, it seemed that this anecdote offered a fresh perspective on some pressing subjects.

Initially, this took the form of a twelve-minute monologue, called The Moth, acted brilliantly by Victor Power on You Tube, directed by Jake for Elysium.

CONTENT WARNING: Video contains themes (references to violence, racism, trauma and warfare) and uses strong language, including expletives, that some viewers may find upsetting or disturbing.

The Moth – as part of The Covid Monologues by Elysium Theatre Company

The format was simple. A static camera focused on the face of the narrator, who recalled an incident on a train when an ex-soldier confessed something harrowing to him, how it altered his life and how, in telling us, that anecdote can never be forgotten.

It played at 26 separate film-festivals as a short, won the best monologue at the Kwanzaa Film festival in New York, gaining, to date, nearly 6000 views. British Theatre Guide reviewer Paul Cunningham wrote of it “the Moth is a short tale but one that lingers”

The next step seemed clear — surely there was a full-length play to be written, drawn from the monologue? To bring the confessor directly into the story and explore the relationship between these two men?

Micky Cochrane as Marius Muller and Faz Singhateh as John Josana, in ‘The Moth’, Northern England Tour, Spring 2025. Photography Victoria Wai.

To end, I’d like to offer a section of the closing speech of John Josana from The Moth: “Apartheid is over in name. In law. But the idea behind it, the willingness, the fear, the madness, that hasn’t gone. — My father always said racism is an illness. Whoever the oppressor, whoever the victim. But that to fall ill, the host must be willing. Welcoming. Joyous with their poison.

This thing of — “race.” Of how we are seen. How perceived. This needless burden that has plagued and ruined, shaped life and discourse for so long. That has determined how people live. Where they live. Who they marry. How they think. What they worship. How they hate.

If they survive.

And it’s still there. The hate. It’s in a gesture. An unconscious thought. A sidestep on a curb. An unwritten rule. An iron-clad law. And yes, down the barrel of a gun. It’s in collusion. And most potent of all it’s in silence. Silence that comes at you like a thunderclap.”

With a tour spanning 25 venues in the North of England during Spring 2025, I invite you to join us on this journey. To book or learn more visit the Elysium Theatre website.

Blog by Paul Herzberg, Playwright and Actor, March 2025.

Reviews for The Moth

“Thoroughly worthwhile… A production that leaves the audience with plenty of food for thought.” – North East Theatre Guide