Disclaimer: Please be advised this blog contains content, including descriptions of and references to torture and suicide, that some readers might find disturbing and/or upsetting.

Individual and Collective Trauma: Seeking Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation

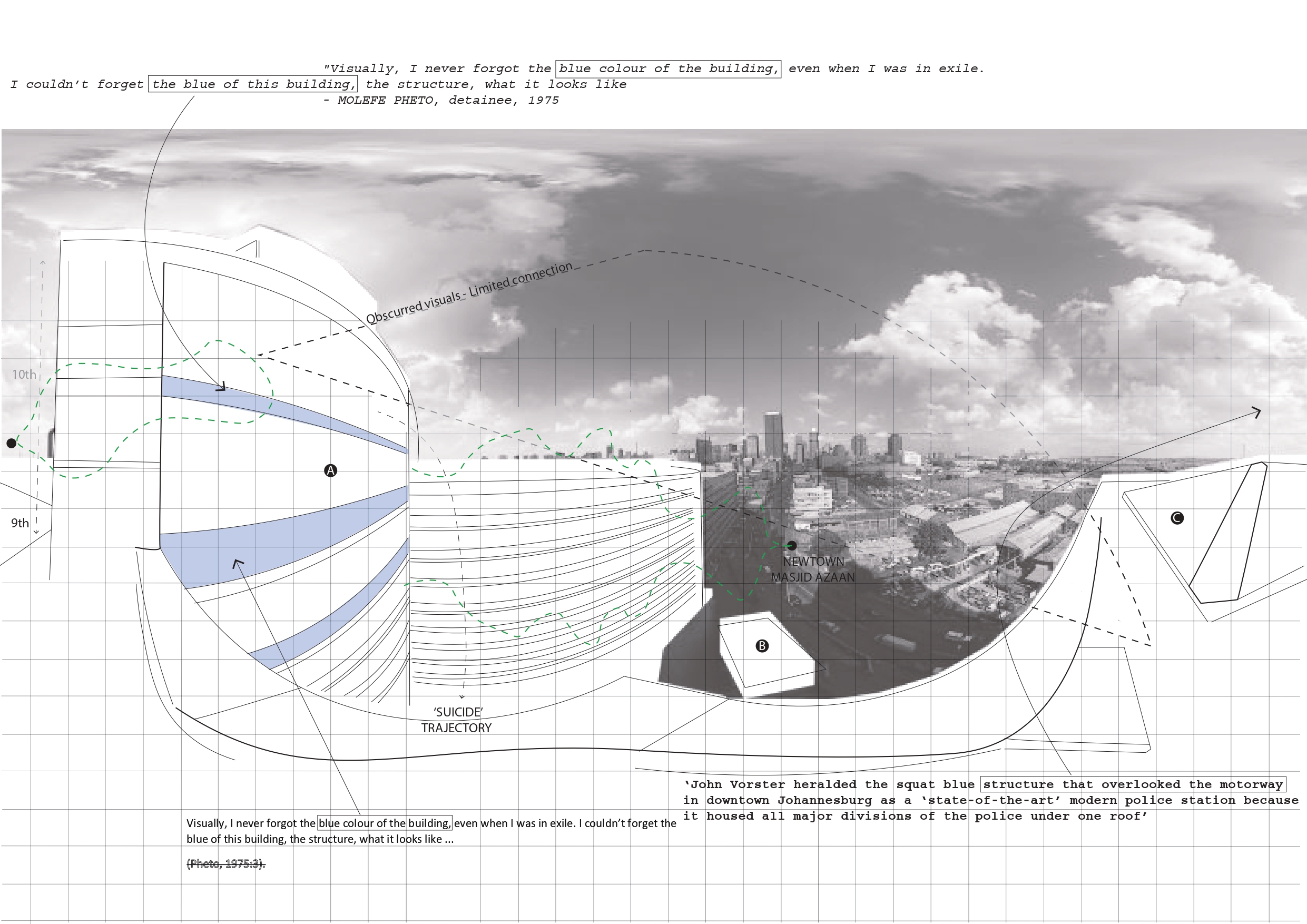

Above Image: Graphical illustration of the ‘suicide trajectory’ from the 10th Floor of John Vorster Police Station. Illustration by Y, Patel inspired by panoramic photographs taken by Craig Matthew (2007).

The Ground-Breaking Timol Case

In October 1974 Ahmed Timol was arrested at a roadblock, handcuffed, and driven to the Newlands Police Station in Johannesburg. The reason for his arrest was that anti-apartheid pamphlets were found in his car. Eventually, the police constructed a report wherein Timol admitted to working with the South African Communist Party in London to overthrow the apartheid regime. Timol’s body was handed over to his family later that month (Myburg, 2017). As the family began the painful task of preparing his body for burial, they noticed that Timol’s nails had been removed, his elbows burnt, his body savagely bruised, and his neck broken. The result of a magistrate’s inquest into his death a few months later found Ahmed Timol to be responsible for his own death – as he had willingly chosen to commit suicide by jumping from the tenth floor of the John Vorster Police Station (Cajee, 2005: 54). No details of torture were mentioned, leaving the apartheid state absolved of any responsibility for Timol’s death (Myburg, 2017).

As with previous deaths in detention, apartheid inquests confirmed police accounts and absolved the Security Branch of wrongdoing. According to police officer Joao Rodriguez’s version of events, Timol committed suicide by jumping out of the tenth floor of John Vorster Police Station. Other deaths-in-detention were ascribed to suicide or accidents, such as hanging or slipping in the shower. At the time, those who knew Timol and were aware of the brutality of the apartheid state police, strongly believed the sequence of events detailed by the police officers to be untrue, however, there was no avenue to appeal the inquest findings.

Years of pressure on the South African justice system eventually resulted in a re-opening of the inquest in 2017. After days spent in court hearings listening to testimonies from pathologists, trajectory specialists, fellow detainees and former Security Branch members, Judge Billy Mothle ruled that Ahmed Timol did not commit suicide but ‘died as a result of having been pushed to fall, an act which was committed by members of the Security Branch with “dolus eventualis” as a form of intent, and prima facie amounting to murder’ (Mothle, 2017). During the inquest spatial consultants, including architects, were brought in to analyse and assist in the court’s decision. The re-opening of the inquest is the first of its kind in South African history and has encouraged families of other death-in-detention inmates to pursue similar legal recourse.

”The Indian asked me to go to the toilet. He was sitting on the chair opposite me. We both stood up and I moved to my left (clockwise) around the table. There was a chair in the way. When I looked up, I saw the Indian rushing around the table in the direction of the window. I tried to get around the table but his chair was in the way. Then I tried to get around the table (anti-clockwise) and another chair was in the way. The Indian already had the window open and was diving through it. When I tried to grab him, I fell over the chair. I could not get him.

(Rodriguez, 1971: 18)

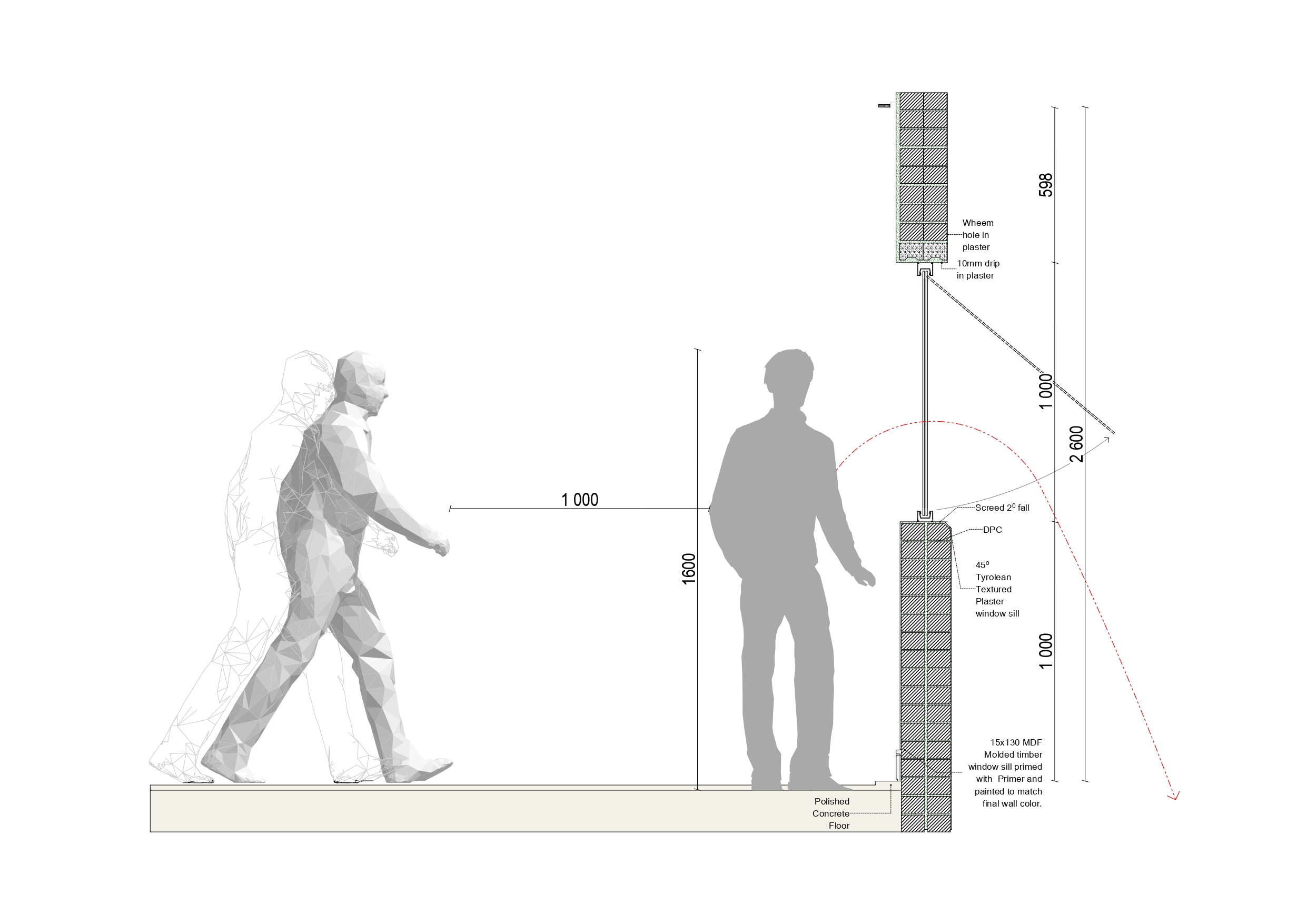

This is the testimony of Joao Rodriguez, the ex-Security Branch officer involved, regarding the events around Timol’s alleged suicide. Rodriguez claimed to have been the only eyewitness to the alleged suicide of Ahmed Timol and was the state’s key witness during the first inquest in 1972. Rodriguez, a white South African of Portuguese descent, worked as an administrative clerk at security police headquarters in Pretoria (Cajee, 2005). After ten years of service to the force, Rodriguez had reached the rank of sergeant. Nearly fifty years after the incident, Rodriguez’s account was deemed improbable and the verdict around Timol’s death was overturned during the inquest. Through the architectural unpacking of the crime scene, it was determined that with Timol’s height (1.6m) and the height of the window (1m), it would have been difficult for him to get through the window, and that the Security Branch officer would have had time to intervene (Statement – High Court of South Africa, Case number 2361/71: 11). The Officer’s version was deemed highly unlikely by the court as both Rodriguez and Timol had been sitting at the interrogation table, only a metre apart – yet Timol had allegedly managed to reach the window; unlatch and open it and exit through it without Rodriguez being able to prevent him. Rodriguez argued that the chair prevented him from getting to Timol in time.

Image: Unpacking the sequence of events leading to the death of apartheid activist Ahmed Timol. Image by: Y Patel

Excerpts taken from chapter contribution (page 151-172) to the Publication, Architecture and Politics in Africa: Making, Living and Imagining Identities through Buildings, edited by Joanne Tomkinson, Daniel Mulugeta and Julia Gallagher.

Architecture and Politics in Africa Free download here

Beyond the Timol Case: What this means for other families pursuing recourse

Timol family Finds Closure GIF. Image by: Y Patel

The Timol family like the Aggett, Hafejee, Haron, Dipale, Mohapi and many others have since successfully pursued, or intend to pursue inquests into the torture and deaths of their relatives. The blanket of silence and secrecy that has shrouded the post TRC amnesty proceedings risk furthering the divide between apartheid victim and aggressor and continues to tighten the shackles of transgenerational trauma. Dr. Najwa Norodien-Fataar and Prof. Aslam Fataar , upon the successful inquest into the death of Imam Haron argued:

”Without formal investigations and acknowledgement by the state, the community may be in a condition of ‘ungrievability.’ In other words, the lack of an explanation and disclosure of torture and killing by the apartheid regime may have prevented affected families from processing deaths. They may struggle to enter a period of mourning and grief, pick up the emotional pieces, and figure out ways of moving forward free from the psychological shackles imposed by the lack of full disclosure and acknowledgment…

These inquests are sought after by families as reconciliation and grief mechanisms, as platforms for interrupting the cycle of transgenerational trauma suffered by families and larger communities.

”…This means that we must find ways of moving the inquest and its outcomes from the court into our community’s institutions, such as churches, mosques, social welfare operations, media, schools, universities, and colleges. This is where we would be able to do the necessary counselling, educational and dialogical work within communities to interrupt and build skills to address community and individual trauma.

The South African social and judicial systems sit at a crossroads, do they deal with these unresolved cases which entails facing the difficult histories of the past, or potentially miss the opportunity to reconcile as the memories of these events fade or are lost? If so, as generations transition, will the shackles of trauma not only remain but continue to impact successive generations?

Written by Yusuf Patel, Intern, via our membership of the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience and in partnership with Newcastle University, July 2023